BACKGROUND TO PORTAL HYPERTENSION AND VARICEAL BLEEDING

Portal hypertension occurs due to a complex interaction between increased resistance in the hepatic microcirculation, increased vascular tone and an imbalance in vasoactive molecules resulting in net vasoconstriction. Increased endogenous vasodilators are produced to compensate with consequent splanchnic arteriolar vasodilation and subsequent increased blood flow in the portal system, further increasing portal pressure[1,2]. Systemic vasodilation and increased cardiac output requiring an expanded blood volume are also associated with these physiological changes.

The resultant portal hypertension leads to the development of varices in about 40% of Childs-Pugh A patients and 60% of those with ascites with an expected incidence of new variceal development of 5% per year[3-5].

CURRENT BURDEN OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION ON ENDOSCOPY SERVICES

Screening

Endoscopy is the gold standard method for screening cirrhotic patients. Current recommendations suggest those with medium to large varices should be treated with B-blockers to prevent bleeding while all others should undergo periodic surveillance endoscopy. Those with compensated cirrhosis and no varices should have endoscopy every 2-3 years while those with small varices should have endoscopy every 1-2 years.

The true incidence and prevalence of cirrhosis in the United Kingdom is unknown. Approximately 4% of the population have abnormal liver tests or liver disease, and 10%-20% of those with one of the three most common liver diseases (non alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease and chronic hepatitis C) develop cirrhosis over 10-20 years[6]. In a city with a population of 250 000, up to 2000 new cases of cirrhosis could be expected over 10-20 years. Thus the demand on endoscopic screening will continue to increase. Mortality from liver disease has increased from 6 per 100 000 population in 1993 to12.7 per 100 000 population in 2000.

Various non invasive methods of assessing portal hypertension have reviewed by Thabut et al[7] Many methods provide an accurate estimation of the presence of severe portal hypertension but not of the presence of moderate portal hypertension in comparison with the Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). These approaches are aimed at evaluating hyperkinetic syndrome (measuring cardiac index, measurement of splanchnic circulation, baroreflex sensitivity, measurig portal blood flow) or evaluating increased intrahepatic vascular resistance (levels of endogenous vasoconstrictors such as endothelin, markers of hepatic fibrosis eg; procollagen III peptide, transient elastography). The only non invasive tools for the detection of oesophageal varices are computed tomographic (CT) scans and oesophageal capsules. Studies have shown CT scanning to be safe and effective and well tolerated with sensitivities ranging from 63% to 93% for the detection of all varices and a sensitivity of 56% to 92% for detection of large varices. When oesophageal assessment for varices by capsule endoscopy is compared to standard endoscopy, it has been shown to have sensitivity of 68% to 100% and specificity of 88% to 100%, with patients significantly preferring capsule endoscopy to standard endoscopy.

CURRENT MANAGEMENT OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION

Pre primary prophylaxis

All cirrhotic patients should be screened at diagnosis. At present there is no indication to use Beta blockers to prevent the formation of varices[8].

Primary prophylaxis

Non-selective beta-blockers are the most commonly used drugs to treat portal hypertension. Propranolol is widely used while nadolol and carvedilol have more recently been shown to have beneficial effects and may be better tolerated in some individuals. Beta-blocker therapy reduces the 2 year bleeding risk from 25% with no treatment to 15% with a reduction in mortality from 27% to 23%. Current consensus does not recommend combination of beta blockers with nitrates in primary prophylaxis[9].

Benefit is seen in treatment of varices greater than 5 mm in diameter[10] With medium to large varices, either non-selective beta-blockers (NSBB) or endoscopic band ligation (EBL) is recommended. Only 30%-40% of patients reduce their portal pressure to greater or equal to 20% from baseline or to under 12 mmHg[11]. The risk of bleeding returns to that of the untreated population on removal of B blocker with a subsequent higher mortality than the untreated population[12]. Variceal band ligation is as effective as propranolol and superior to isosorbide mononitrate in preventing first variceal bleeds[13].

Secondary prophylaxis

Variceal band ligation combined with a beta-blocker is recommended as secondary prevention for oesophageal variceal haemorrhage. Band ligation is safer and more effective than sclerotherapy in treatment of recurrent bleeding from oesophageal varices[14]. Failure of standard treatment occurs in 10%-15% of acute variceal bleeds.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can be used to prevent variceal rebleeding and is more effective in preventing rebleeding than endoscopic therapy[15,16]. In a recent study, the early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding has been assessed- Patients presenting with an acute variceal bleed were treated with vasoactive therapy and endoscopic therapy (band ligation or sclerotherapy) and then randomised to early TIPS with an extended polytetraflouroethylene stent within 24-72 h of presentation or continuation of vasoactive treatment, beta blockers and longterm endoscopic band ligation. It was concluded that patients with acute variceal bleeds with a hepatic venous pressure gradient of 20 mmHg or above are at a high risk of treatment failure and the early use of TIPS in these patients is associated with a significant reduction in treatment failure and mortality[17].

Pharmacological management of acute variceal bleeding

The primary aim is to correct hypovolaemia, resuscitate the patient and obtain haemostasis hence preserving tissue perfusion and maintaining haemodynamic stability. Prolonged hypovolaemia increases the risk of complications such as infection and renal failure which are associated with higher mortality and rebleeding rates[18,19].

Early administration of vasoactive drugs facilitates endoscopy, improves control of bleeding and reduces 5 d rebleeding rates[20-22]. In addition, drug therapy will improve the outcome even if commenced after endoscopic sclerotherapy or band ligation[23,24]. Antibiotics and vasoactive drugs such as glypressin and somatostatin are the only drugs shown to improve survival in an acute variceal bleeding episode and should be continued for five days to prevent early rebleeding.

Conflicting results have been obtained in studies assessing the efficacy of somatostatin and long acting analogues in control of variceal haemorrhage- modest reductions in hepatic blood flow and wedged venous pressure have been reported by some groups, others have found no effect on portal pressure[25,26]. Azygos blood flow as a measure of collateral blood flow has been shown to reduce with somatostatin. In a meta-analysis, somatostatin proved to be effective in controlling variceal haemorrhage, without a beneficial effect on mortality. When compared with sclerotherapy, treatment with somatostatin and octreotide resulted in fewer side effects with equal efficacy. Finally, when combined with endoscopic therapy, somatostatin, octreotide and vapreotide proved to be more effective than placebo[5]. Vasoactive therapy with a single agent is as effective as endoscopic therapy[27-29].

Endoscopic management of acute variceal bleeding

Endoscopic therapy should be performed within 12 h of admission. A meta-analysis of seven placebo-controlled trials showed that variceal band ligation therapy was superior to sclerotherapy in terms of rebleeding (all-cause mortality and death due to bleeding in patients with bleeding oesophageal varices)[30]. In the case of uncontrollable haemorrhage, balloon tamponade may be necessary as a bridge to more definitive treatment but should ideally be used for no more than 24 h. When TIPS or other shunts are not possible, novel therapeutic options include tissue glue (even in oesophageal varices) and in future, self expanding oesophageal metal stents may have a role in refractory oesophageal variceal bleeding[31].

Endoscopic follow-up after variceal bleeding

Recurrent variceal bleeding can be as high as 50% within the first 24 h and 80% within one year[32]. Patients with cirrhosis who have had a bleed should receive a combination of beta blockers and band ligation as it results in lower rebleeding compared to either therapy alone[7].

A meta-analysis of 895 patients in 12 trials comparing propranolol with placebo in the secondary prevention of variceal haemorrhage found propranolol monotherapy more effective than placebo in reducing risk of death and rebleeding however, only 30%-40% of patients reduce their portal pressure to greater or equal to 20% from baseline or to under 12 mmHg[10] and the risk of bleeding returns to that of the untreated population on removal of B blocker with a subsequent higher mortality than the untreated population[11]. TIPS should be considered to prevent rebleeding when combination pharmacological and band ligation therapy are not available, cannot be tolerated or fail.

In a recent meta-analysis by Li et al[33], controlled trials evaluated the efficacy of EBL vs pharmacological therapy for the primary and secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Six hundred and eighty seven patients from six trials were reviewed comparing EBL with beta-blockers plus isosorbide mononitrate for secondary prevention. There was no effect on either gastrointestinal bleeding [RR 0.95 (95% CI: 0.65 to 1.40)] or variceal bleeding [RR 0.89 (95% CI: 0.53 to 1.49)]. The risk for all-cause deaths in the EBL group was significantly higher than in the medical group [RR 1.25 (95% CI: 1.01 to 1.55)]; however, the rate of bleeding related deaths was unaffected [RR 1.16 (95% CI: 0.68 to 1.97)] and it was concluded that betablockers plus isosorbide mononitrate may be the best choice for the prevention of rebleeding.

Lo et al[34] comment on the long-term effectiveness and survival of endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) with nadolol and ISMN in the prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices. The study demonstrated that EVL was definitely better than combination drug therapy in terms of prevention of rebleeding from oesophageal varices. Blood requirements were slightly lower in the patients who underwent repeated EVL than in those who received nadolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate (ISMN). On the other hand, the survival in patients treated with combination drug therapy appeared to be better than in those treated with repeated EVL. Nonetheless, b-blockers had to be discontinued in up to 25% of patients because of adverse effects. EVL is the preferred approach among those patients in whom b-blockers fail or are intolerable

Following successful haemostasis in an acute variceal bleed, Silvano et al[35] reported the mean number of endoscopy sessions required for variceal obliteration following an acute variceal bleed was 2.8 with a range of 1-7.

HEPATIC VENOUS PRESSURE GRADIENT MEASUREMENT

Background

Portal pressure, in chronic liver diseases, is commonly measured by the HVPG, defined as the difference between wedged (occluded) and free hepatic venous pressures with normal values ranging between 1 mmHg and 5 mmHg. It is an acceptable indirect measurement of portal hypertension, because wedged hepatic venous pressure is very close to portal venous pressure in most chronic liver diseases, particularly in alcoholic and viral (B and C) cirrhosis[36-39]. It thus acts as a marker of transmural variceal pressure. HVPG is reproducible and the best predictor of the complications of portal hypertension in adult cirrhotics. Varices develop at a HVPG of 10-12 mmHg with the appearance of other complications with HPVG > 12. Variceal bleeding does not occur in pressures under 12 mmHg[40-43]. HPVG > 20 mmHg measured early after admission is a significant prognostic indicator of failure to control bleeding varices, indeed early TIPS in such circumstances reduces mortality[44].

The procedure is performed under local anaesthetic via the internal jugular vein using a balloon catheter. Techniques have been improved since HVPG measurement was first proposed substituting the use of a straight catheter with a balloon catheter positioned into a large hepatic vein which can be inflated to block blood flow and deflated allowing measurement over a larger liver volume making measurement easier, quicker to perform and repeatable across different liver areas and between different examiners.

It is a safe procedure with Bosch et al[45] reporting no complications in over 10 000 procedures. Thabut et al[7] reported minor complications in < 1% of 13 000 procedures, mainly transient cardiac events. Midazolam can be used for conscious sedation and will not alter hepatic pressures. At present, the HVPG is not part of the routine investigation in chronic liver disease and is not incorporated in prognostic scores.

Use of HVPG

At present, the main indications of HVPG measurement in adults are the diagnosis of portal hypertension, the assessment of the effects of drug therapy, the preoperative evaluation for liver resection surgery in patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, the quantification of disease progression/regression of chronic liver disease due to infection with hepatitis C or B virus and identification of the need for TIPS revision[46].

Using HVPG to achieve therapeutic targets

Changes in portal venous pressure induced by drugs are similarly reflected in wedged hepatic venous pressure, and therefore the HVPG is an adequate measure of drug effects on portal pressure. The risk of primary bleeding and rebleeding is much lower in cirrhotic patients with a good response to treatment[43,47-49] and baseline and repeat measurements of HVPG have been recommended for the management of patients with cirrhosis in the setting of pharmacologic prophylaxis of variceal bleeding.

A reduction in HVPG of more than 20% from baseline or a final HVPG less than 12 mmHg, results in a reduction of the complications of cirrhosis, improved survival and reduction in variceal size.51[10,50-52]. Reaching these targets may also lead to improvement in the development or accumulation of ascites, sbp, hepatorenal syndrome and subsequent death[53,54]. This target is achieved in only approximately 30% of patients. Even reduction of more than 10% from baseline reduces the risk of first variceal bleeding. HVPG response to intravenous propranolol may also be used to identify responders to beta blockers however further studies are required[7].

Current pharmacological therapy used in the treatment of portal hypertension only addresses the increased portal blood flow component of the syndrome. The intrahepatic resistance component has yet to be widely explored with new drugs. For this purpose, repeated HVPG measurements may be necessary until less invasive methods of evaluating portal pressure become available.

HVPG monitoring in primary prophylaxis

HVPG is not routinely used in the pre-primary prophylaxis other than in the context of clinical trials.

In primary prevention, only 30%-40% of patients with non selective beta blockade or endoscopic band ligation for primary prophylaxis will lower their portal pressure by more than or equal to 20% from their baseline or < 12 mmHg and it is well accepted that in these cases, there is an increased risk of bleeding-Merkel et al[47] reported that the cumulative probability of primary variceal bleeding was significantly higher among hemodynamic non responders to B-blockers. Furthermore, Groszmann et al[43] reported none of the patients who achieved an HVPG of ≤ 12 mmHg during subsequent measurements experienced a hemorrhage.

HVPG measurement could be used as the investigation of choice in those those patients who have confirmed cirrhosis in place of endoscopy for intitial variceal screening. In those with elevated pressures, primary medical prophylaxis could be commenced with subsequent close monitoring of HVPG thus negating the need for endoscopy at this point.

HVPG monitoring in secondary prophylaxis

Early HVPG measurement has been identified as an independant predictor of short term prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with standard endoscopic and pharmacological management and patients not achieving the suggested reduction targets in HVPG have a high risk of rebleeding despite endoscopic ligation. These patients may not derive significant overall mortality benefit from endoscopic interevention alone and may require TIPS or liver transplantation[49]. In the setting of an acute bleed, HVPG greater than 20 mmHg at endoscopy is one of the variables most consistently found to predict 5 d treatment failure. 10%-15% of patients in the setting of an acute variceal bleed will require repeat endoscopic therapy.

TIPS can be used to prevent variceal rebleeding and is more effective in preventing rebleeding than endoscopic therapy[16]. Early HVPG measurements following a variceal bleed can help to identify those at risk of treatment failure who may benefit from early intervention with TIPS.

Garcia-Pagan et al[17] have shown that in patients with cirrhosis, in the setting of an acute variceal bleed, and at high risk of treatment failure with a HVPG of ≥ 20 mmhg, the early use of TIPS is associated with a significant reduction in treatment failure and mortaility. This in return, reduces the number of endoscopies being performed in an effort to achieve subsequent haemostasis in the event of a rebleed.

HPVG monitoring is also useful to adapt medical therapy according to response. Such as the addition of ISMN to b-blockers which enhances the fall in portal pressure achieved using only b-blockers and this combined therapy has shown efficacy in preventing variceal rebleeding. Responders to b-blockers have no further decrease in HVPG with the addition of vasodilators and the beneficial effects are restricted to nonresponders[55,56].

Villaneuva et al[55] carried out a study on cirrhotic patients following a variceal bleed to assess the value of HVPG-guided therapy using nadolol + prazosin in nonresponders to nadolol + ISMN compared with a control group treated with nadolol + ligation. A Baseline haemodynamic study was performed and repeated within 1 mo. In the guided-therapy group, nonresponders to nadolol + ISMN received nado- lol and carefully titrated prazosin and had a third haemodynamic study. Nadolol + prazosin decreased HVPG in non responders to nadolol + ISMN (P < 0.001). 74% of patients were responders in the guided-therapy group vs 32% in the nadolol + ligation group (P < 0.01). The probability of rebleeding was lower in responders than in nonresponders in the guided therapy group (P < 0.01), but not in the nadolol + ligation group (P = 0.41). In all, 57% of nonresponders rebled in the guided-therapy group and 20% in the nadolol + ligation group (P = 0.05). This study suggests the use of ligation to rescue non responders who have had their medical therapy optimized by close HVPG monitoring.

Therefore, we recommend all patients presenting with variceal haemorrhage should undergo HVPG measurement and those with a gradient greater than 20 mmHg should be considered for early TIPS. The remainder should have a trial of B-blockade, either intravenously during the initial pressure study with assessment of response or oral therapy with repeat HVPG six weeks later. As nonresponders to drugs tend to rebleed early, many patients rebleed before their hemodynamic response is evaluated. Early hemodynamic measurements are recommended.

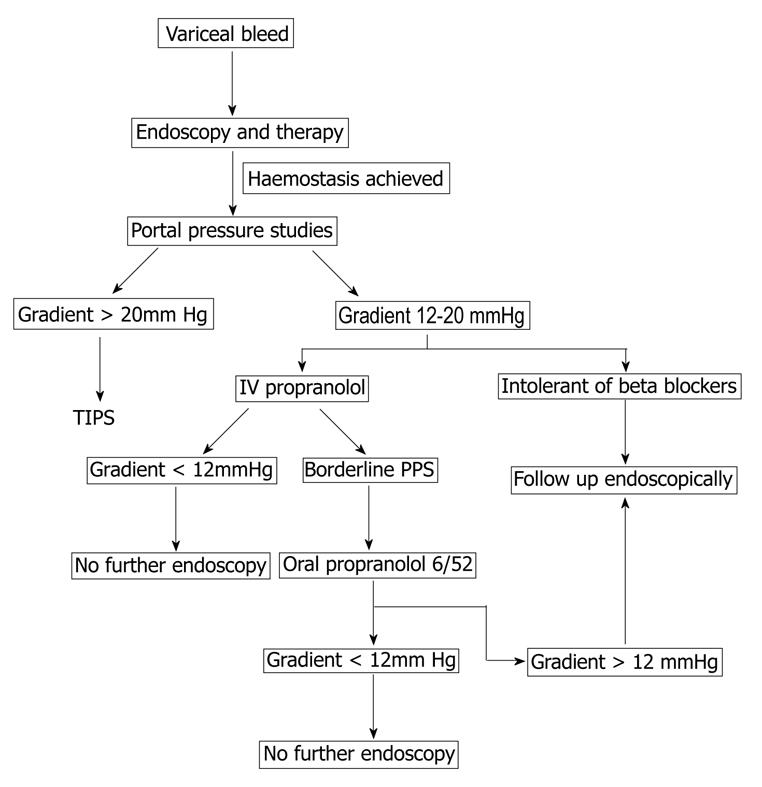

A potential algorthym for the use of portal pressure measurement in management of variceal bleeds is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Algorithm for the use of portal pressure studies in the management of portal hypertension.

TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Prognostic value of HVPG

This remains under debate. HVPG response correlates with morbidity and mortality from portal hypertension. Some authors have proposed that HVPG measured after bleeding[57,58] or sequential HVPG recordings may predict survival, whereas others have not found any predictive value of HVPG for survival[59,60]. As the level of portal hypertension has been correlated with both histologic damage and degree of liver failure[61] it could be proposed that HVPG be used as a prognostic indicator along with Child Pugh, Meld and UKELD Scores[62]. Increasing HVPG has also been associated with increased annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma development.

Limitations of HVPG

Although HVPG measurement is safe and relatively simple, it is invasive and some difficulties still exist in relation to its use as a screening tool. HVPG calculation must be standardized. The hemodynamic data available is difficult to interpret with variation seen in treatment used, percentage of patients with alcoholic liver disease, time of follow-up, percentage of patients in Child’s class C, and in the interval of time after which the second HVPG measurement was performed[10,63-65]. A significant relationship was found between a longer time interval between two HVPG measurements and a lower benefit from HVPG reduction[66]. Furthermore, HVPG is likely to decrease with alcohol abstinence and this will affect results of such studies. Further clinical trials are required to evaluate prospectively the prognostic value of HVPG changes for the risk of bleeding and to assess HVPG guided therapy. Trials assessing pharmacological management in primary prophylaxis should include HVPG measurements.

HVPG measurement is expensive with an estimated cost of US $4000 per procedure due to the cost of equipment (radiology apparatus, pressure recorder and monitors), one use only products (venous introducer, catheter to reach hepatic vein, guide wire, balloon catheter, disposable pressure transducer and contrast), personnel to carry out the procedure and required observation period in hospital following the procedure[46].

CONCLUSION

As the prevalence of cirrhosis continues to rise in the western world, portal hypertension plays a crucial role in the transition from the preclinical to the clinical phase of cirrhosis with the subsequent complications being both a major cause of death and liver transplantation. It also places a large burden on the health service in terms of resources required to deal with the complications of cirrhosis. The ideal scenario is that portal hypertension is detected early in a cost effective manner prior to complications developing.

Universal endoscopic screening of cirrhotics for varices may mean a lot of unnecessary procedures as the presence of oesophageal varices is variable with prevalence ranging from 24%-80% and this puts a large time and cost burden on endoscopy units to carry out both screening and subsequent follow up of variceal bleeds[67]. Up to 50% may not have developed varices 10 years after the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Studies have shown a lack of agreement between endoscopists in grading the size of varices[68-70] with endoscopic experience being one of the variables.

Endoscopy may be uncomfortable, invasive, costly and time consuming and patient preference is obviously paramount relating to compliance and hence to the success of a screening programme which in turn has an impact on the services required and overall cost effectiveness. As the majority of patients are asymptomatic and require a procedure that they may judge as unpleasant, may require sedation and has associated complications, compliance can be low and this is a major factor in the effectiveness of screening programmes. It is therefore essential that studies in this area are ongoing to identify possible alternatives to endoscopy as a screening tool for oesophageal varices.

A less invasive method to identify portal hypertension and hence those requiring endoscopy would prove beneficial both in reducing the number of screening endoscopies performed and also identifying those at high risk of bleeding therefore allowing earlier prophylactic measures to be applied with the aim to reduce subsequent acute bleeding presentations. Various methods have been studied but no alternative for endoscopy has yet been found.

Not all those who initially respond to medical therapy remain good responders and data beyond one year follow up is lacking hence longer term studies are essential as worsening HVPG despite beta blocker treatment is a significant predictor of death independent of Child Pugh/MELD scores[46]. Villanueva et al[71] who report follow up at 24 mo of cirrhotic patients with oesophageal varices undergoing HVPG monitoring whilst undergoing primary prevention with initial IV propranolol and subsequent treatment with nadolol suggest an HVPG reduction of ≥ 10% from baseline should be the target and that the acute reponse to beta blocker can be used to predict the long term risk of first bleeding wth acute responders having a significantly lower risk of both first variceal bleeding and development of ascites however further longterm studies are required.

In a debate regarding the use of HVPG monitoring as a guide for prophylaxis and therapy of bleeding and rebleeding, Thalheimer et al[72] state that relying on haemodynamic response status cannot be recommended in current clinical practices due to discrepancies in the studies to date as a result of variation in treatment combinations, aetilogy of liver disease, Childs Pugh scoring of patients, variation in timing of follow up and inaccurate recording of responder status or repeat HVPG measurements. This clearly indicates the need for ongoing research in this area. The number of patients required to carry out a randomized control trial comparing beta blocker therapy and HVPG monitoring with unselected beta blocker treatment are large (n = 600) and have financial and resource implications for a study group to take on[73].

Raines et al[74] proposed a model to evaluate the cost and efficacy of routine HVPG measurement to guide secondary prophylaxis of recurrent variceal bleeding- whilst combination therapy (beta blockers and band ligation) with two HVPG measurements was expensive, it became cost-effective at 1 year compared with standard prophylaxis with combination pharmacotherapy. The cost-effectiveness of haemodynamic monitoring to guide secondary prohylaxis of recurrent variceal bleeding is highly dependent on local hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement costs, life expectancy and re-bleeding rates.

We propose that by introducing portal pressure studies into a management algorithm for variceal bleeding, the number of endoscopies required for further intervention and follow up can be reduced leading to significant savings in terms of cost and demand on resources.Further studies are required to assess the cost effectiveness of HVPG measurements in the management of variceal bleeding.

With the development of further pharmacological interventions in the management of variceal bleeding, portal pressure studies are likely to become increasingly important in assessing the risk of bleeding and prognosis and this is an area that requires further study.